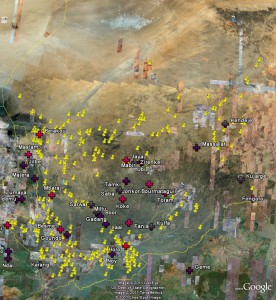

I’ve finally been able to obtain the dataset on which UNESCO’s interactive Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger is based. ((Thanks, Kai.)) In the map below, which you’ll be able to see bigger if you click on it, you can see Chad’s endangered languages (brighter red means more endangered), mashed up with germplasm from Chad listed in Genesys.

Would it be sensible to give particular priority for germplasm collecting to areas where languages are threatened with extinction?

Say more. Why would you prioritize germplasm collecting in areas where languages are threatened with extinction? Instinctively one does feel there should be a link but is there?

I don’t know. It’s a hypothesis, I guess. Certainly, if the language is threatened, indigenous knowledge will be threatened, including IK on agrobiodiversity. And that is surely the first step on the road to losing the agrobiodiversity itself.

I do agree with Luigi. There is knowledge that is particular and specific to a given culture and that of a particular language is certainly a nest for that niche culture. Besides, particular traditional varieties are closely connected to niche cultures. If there isn’t a very direct link there’s certainly a good chance of endangered germplasm and associated endangered language. Worth digging …

I’ve been argumenting with some colleague breeders that at specific levels of scale, ethnic background may be a more potent precursor/predictor of agrobiodiversity than agro-ecologies. Some recent studies hint at that. I’ve been trying to join the ethnologue.com database with detailed shapefiles of dominant linguistic groups of Africa at a fairly detailed level, but lack time/resources to dig in further. If someone, self-funded (PhD student…) is interested in an in-depth investigation I’d be willing to spend some time towards joint publications! Or better, host him/her at SotubaGIS, Bamako, Mali.

Sibiry

—

Pierre C. Sibiry Traore, Remote Sensing Scientist & Head, GIS

Intl. Crops Res. Inst. for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT)

c/o SotubaGIS, LaboSEP, IER-Sotuba, POB320, Bamako, Mali

Tel: +223 20223375 (until 3/20/2011: +91 04030713753)

http://www.icrisat.org / http://www.ier.ml / http://www.ufl.edu

Dear Luigi,

You have a very good point as the degree of threat to a language must be a very strong indicator for the loss of a culture and with it the use and knowledge of the mananegt and use of agricultural biodiversity. It would certainly be an important component of the “early Warning System” that is being discussed to be put in place.

Jan

Dear Luigi,

I agree completely with your point. More specifically, we can be sure that local languages embody knowledge about plants in all the areas that matter to plant breeding: naming, production, storage, distribution, cooking, and nutritional and medical value. For most minor languages, whether threatened or not, there is usually very little recorded detail of usage with respect to plants.

Furthermore, minority ethnic groups often reside in geographically isolated locations (or habitats) such as higher mountains and valleys, where mono-cultural agricultural production has had less opportunity to take root and displace local crop varieties and local wild vegetation.

I would expect that the key linguistic indicator is not threat level, but speaking population size – not too large (likely to be associated with monocultural production systems) and not too small (likely to have a very restricted geographical range and knowledge of a relatively limited range of crops and wild plant resources).